-40%

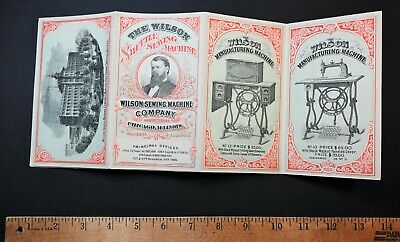

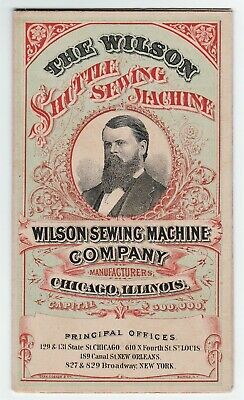

RARE Catalog Brochure Trade Cards 1874 Wilson Shuttle Sewing Machine 5 7 8 9 12

$ 183.74

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

RARE Original Advertising Trade Card Brochure / CatalogFolds open to Large Sheet

The Wilson Sewing Machine Company

Chicago, Illinois

ca 1874

For offer, a nice old piece of advertising ephemera. Fresh from an estate in Upstate / Western NY. Never offered on the market until now.

Vintage, Old, antique, Original -

NOT

a Reproduction - Guaranteed !!

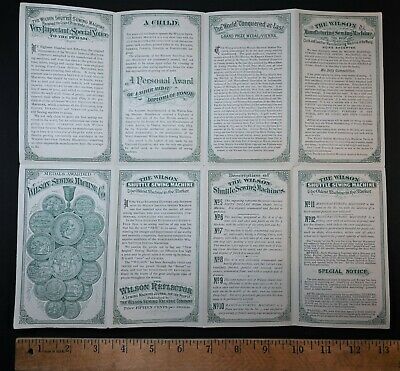

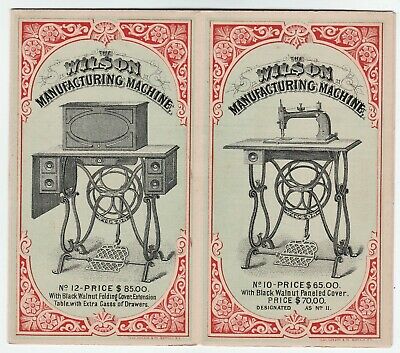

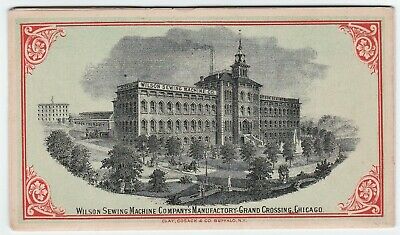

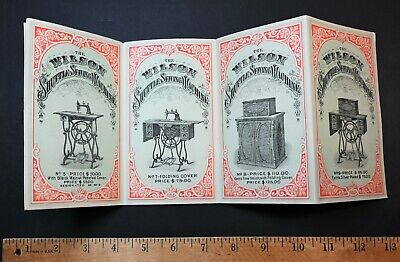

Nice color chromolithograph graphics. Lithograph Printer imprint of Clay, Cosack & Co., Buffalo, NY. I could only locate one other of these, listed at 5. 16 panels - Model no 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 listed, and some shown with illustration. Wilson Manufacturing Company. Black walnut, extension table, drawers, etc. Factory building shown on back in Grand Crossing. This came from an old store with other items from the period. When open measures 13 1/4 x 11 1/2 inches. Folds to smaller size. In very good to excellent condition. Will be sent folded up. Please see photos for details.

If you collect Americana advertisement ad, 19th century American history,

Victorian trade card related, farming, agriculture, industry, etc., this is one you will not see again soon. A nice piece for your paper or ephemera collection. Perhaps some genealogy research information as well.

Combine shipping on multiple bid wins!

2156

Wheeler & Wilson was an American company which produced sewing machines.

Overview

Allen B. Wilson in 1849 made possible one of the world's greatest industries, and the sound administrative policy of Nathaniel Wheeler and his associates was responsible for the transformation of the industry from the modest confines of 1854 in Watertown, Connecticut, shown in the accompanying illustration, to the plant in Bridgeport, employing about 2,000 hands in 1905.[1]

Beginnings

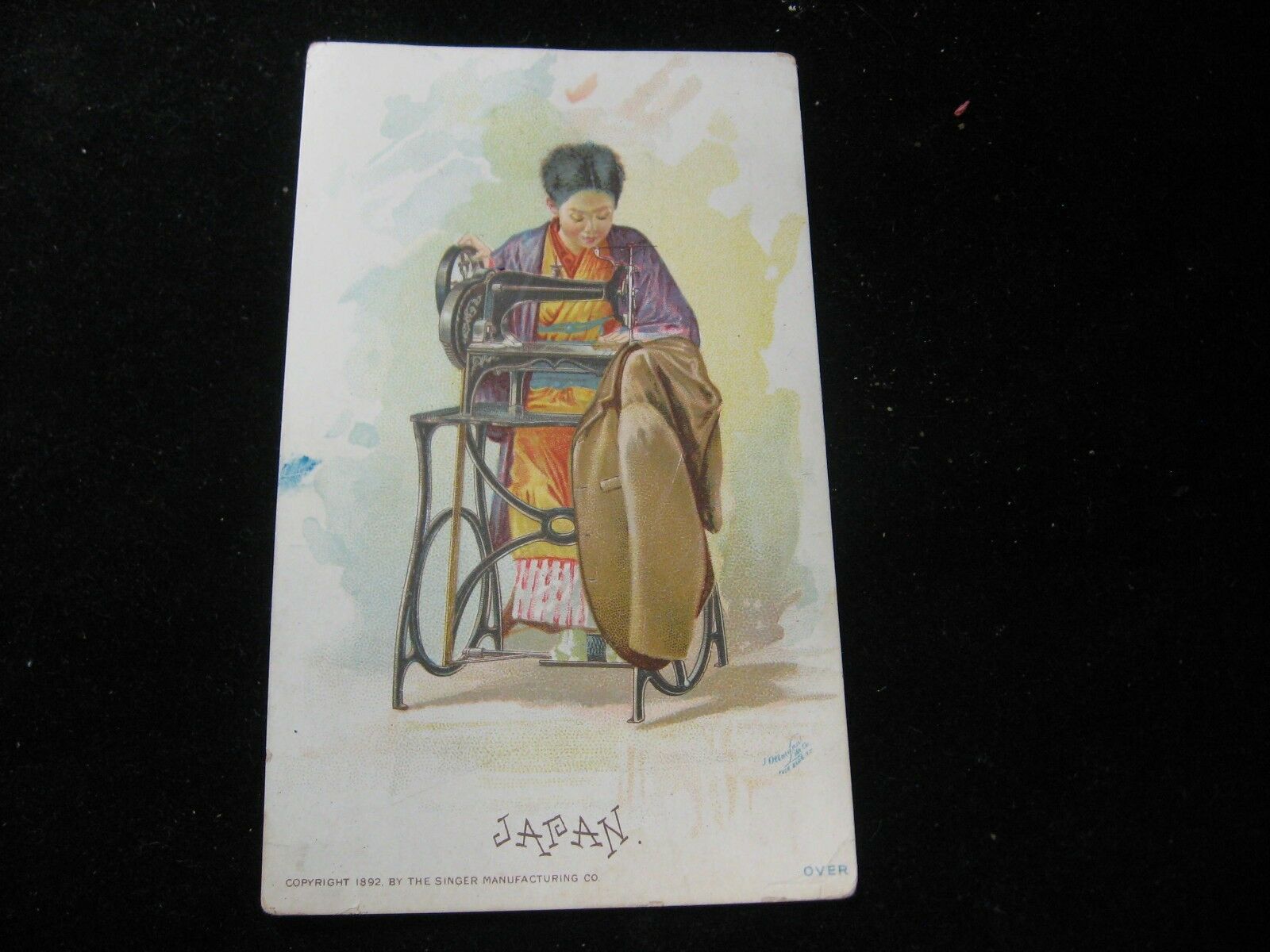

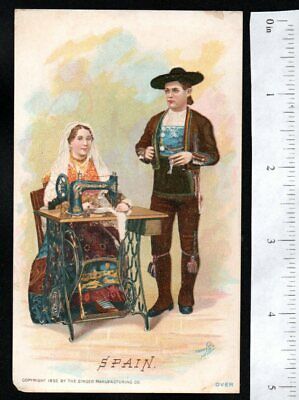

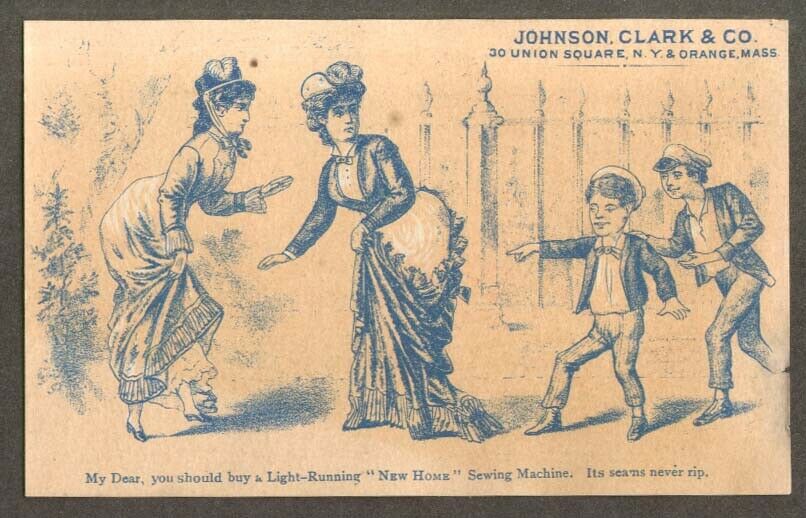

Advertisement of Wheeler & Wilson (1875)

Mr. Wilson first conceived the idea of a sewing machine while engaged in his trade as a journeyman cabinet maker at Pittsfield, Massachusetts. After months of application he constructed the first practical sewing machine and obtained a patent November 12, 1850. Other improved machines and patents followed, and during one of the exhibitions of his invention in New York in 1850, Nathaniel Wheeler became interested.[2] Mr. Wheeler was then manager of the firm of Warren, Wheeler & Woodruff in Watertown, Connecticut, and foreseeing a great field for these machines, succeeded in forming a co-partnership for their manufacture at Watertown, known as Wheeler, Wilson & Company, which name was changed October 5, 1853, to The Wheeler & Wilson Manufacturing Company, with a capital stock of 0,000. The following officers, who were among the incorporators were, Alanson Warren, President; George P. Woodruff, Secretary and Treasurer; and Nathaniel Wheeler, General Manager. On the resignation of Mr. Warren in 1855, Mr. Wheeler succeeded to the presidency, continuing as general manager also, both of which offices he held until his death, December 31. 1893.

In 1856 the company moved from Watertown, Connecticut to Bridgeport, Connecticut, occupying the old Jerome Clock Company's factory.

The company's capital stock was increased in July, 1859, to 0,000, and June 29, 1864, the company was granted a special charter by the State of Connecticut, and the capital stock was further increased to .000,000. After Nathaniel Wheeler's death in 1893, his son, Samuel II. Wheeler, succeeded to the presidency. His official associates were George M. Eames, vice-president, and Newton H. Hoyt. secretary and treasurer.

The other general offices of the company were held for many years by Isaac Holden as vice-president, William H. Perry as general superintendent, secretary and treasurer, and Frederick Hurd as secretary and treasurer.

Awards

The company won a number of Prize Medals, including at the Industrial Exposition, Paris 1861, International Exhibition of London 1862, and the Exposition Universelle, Paris 1868, 1878 and 1889.

At the Vienna Exhibition of 1873, from over 81 competitors from all parts of the world, the owners of Wheeler & Wilson were awarded the Imperial Order of Francis Joseph, received the Grand Medals of Progress and of Merit, and several medals went to employees. r Other awards received were the Gold Medal of Honour of the American Institute, New York, in September 1873, the Gold Medal at Maryland Institute in October, and a Silver Medal (the highest premium for Stitching Leather at Georgia State Fair in November 1873, the judges of the various Agricultural shows in the United States have endorsed these favourable verdicts by conferring similar awards upon the company.

In July 1874, the jury awarded the First Prize, a silver cup, on account of the "ease of working, the little noise, speed of executing work, and durability of the sewing machines made by the Wheeler & Wilson Manufacturing Company.", at the Bury Agricultural Show in August 1874 the first prize, at the Manchester and Liverpool Agricultural Show on September 10, 1874 the Society's Silver Medal for "excellence of manufacture, progress and novelty in mechanism, and superiority of work done by it." and at the Cheshire Agricultural Society's Show in Warrington on September 23, 1874 the first prize.

Takeover

Singer Corporation took over the Wheeler and Wilson Manufacturing Company in 1905.[3] Singer continued to produce the Wheeler and Wilson #9 model sewing machine under its own brand name until at least 1913.[3][4]

Wilson sewing machines

Wilson sewing machine earliest model filed in Patent Office November 12, 1850

Wheeler & Wilson four-motion feed sewing machine from 1852

Allen B. Wilson's achievement was in the area of inventing and perfecting sewing machines. Two of those were considered the most ingenious and beautiful pieces of mechanism: the rotating hook and the four-motion feed. He claims to have conceived the idea of a sewing machine in 1847. His first machine was built during the spring of 1849, while he was in the employ of a Mr. Barnes, of Pittsfield, Mass., a cabinet maker. In the same year he built a second and better machine, and "up to this time," says, "I had never seen or heard of a sewing machine other than my own." He sold a one-half interest in the invention to Joseph N. Chapin, of North Adams, and with the proceeds took out his first patent, which bore the date November 12, 1850. It formed a lock stitch by means of a curved needle on a vibrating arm above the cloth plate, and a reciprocating two-pointed shuttle traveling in a curved race below the plate. The feed motion was obtained by the two metal bars which are seen intersecting above the shuttle race. The lower bar, called the feed bar, had teeth on its upper face, and by means of a transverse sliding motion it moved the cloth, which was placed between the two bars, the desired distance, as each stitch was made.[5]

In 1851 Wilson patented his famous rotating hook, which performed the functions of a shuttle by seizing the upper thread and throwing its loop over a circular bobbin containing the under thread. 'This simplified the construction of the machine by getting rid of the reciprocation motion of the ordinary shuttle, and contributed to make a light tool silent running machine, eminently adapted to domestic use.[5]

Wheeler and Wilson Number 3 Sewing Machine from about 1872

In 1852 Mr. Wilson patented his four-motion feed, which, in combination with a spring presser foot. The feed bar, as its name indicates, had four distinct motions, two vertical and two horizontal. It was first raised by the action of an eccentric on the driving shaft, then carried forward by a cam formed on the side of the eccentric (by which operation the work was shifted the desired distance), then it dropped, and finally it was drawn back by a spring to its original position. This machine used the curved needle and embodies the rotating hook and the four-motion feed. The latest type of this machine used a vertical needle bar and a straight needle.[5]

Wilson had the good fortune soon after securing his patent to interest Nathaniel Wheeler, a young carriage maker who possessed some capital, in his machine, and out of this connection grew the great house of Wheeler & Wilson. Unquestionably, the association of Mr. Wheeler with the sewing machine at the very inception of the industry was very largely answerable for its early and rapid success. It is rarely that the inventive and the commercial instinct are combined in the same man. It is certain they were not in Wilson. Wheeler, on the other hand, was eminently qualified by his wisdom, tact, and engaging presence to promote the interests of the new device. He succeeded in interesting some of the wealthy capitalists of the day, and the successful career of the Wheeler & Wilson establishment was a tribute to his undoubted business ability.[5]

A sewing machine is a machine used to sew fabric and other materials together with thread. Sewing machines were invented during the first Industrial Revolution to decrease the amount of manual sewing work performed in clothing companies. Since the invention of the first working sewing machine, generally considered to have been the work of Elias Howe, and Englishman Thomas Saint in 1790,[1] the sewing machine has greatly improved the efficiency and productivity of the clothing industry.

Home sewing machines are designed for one person to sew individual items while using a single stitch type. In a modern sewing machine the fabric easily glides in and out of the machine without the inconvenience of needles and thimbles and other such tools used in hand sewing, automating the process of stitching and saving time.

Industrial sewing machines, by contrast to domestic machines, are larger, faster, and more varied in their size, cost, appearance, and task.

History

Invention

Charles Fredrick Wiesenthal, a German-born engineer working in England was awarded the first British patent for a mechanical device to aid the art of sewing, in 1755. His invention consisted of a double pointed needle with an eye at one end.[2]

Newton Wilson's copy of Saint's sewing machine.

Thomas Saint's chain stitch used on the first ever complete sewing machine design for leather work. An awl preceded the eye pointed needle to make a hole in preparation for the thread.

In 1790, the English inventor Thomas Saint invented the first sewing machine design, but he did not successfully advertise or market his invention.[3] His machine was meant to be used on leather and canvas material. It is likely that Saint had a working model but there is no evidence of one; he was a skilled cabinet maker and his device included many practically functional features: an overhanging arm, a feed mechanism (adequate for short lengths of leather), a vertical needle bar, and a looper.

His sewing machine used the chain stitch method, in which the machine uses a single thread to make simple stitches in the fabric. A stitching awl would pierce the material and a forked point rod would carry the thread through the hole where it would be hooked underneath and moved to the next stitching place, where the cycle would be repeated, locking the stitch.[4] Saint's machine was designed to aid the manufacture of various leather goods, including saddles and bridles, but it was also capable of working with canvas, and was used for sewing ship sails. Although his machine was very advanced for the era, the concept would need steady improvement over the coming decades before it could become a practical proposition. In 1874, a sewing machine manufacturer, William Newton Wilson, found Saint's drawings in the London Patent Office, made adjustments to the looper, and built a working machine, currently owned by the London Science Museum.

In 1804, a sewing machine was built by the Englishmen Thomas Stone and James Henderson, and a machine for embroidering was constructed by John Duncan in Scotland.[5] An Austrian tailor, Josef Madersperger, began developing his first sewing machine in 1807 and presented his first working machine in 1814. Having received financial support from his government, the Austrian tailor worked on the development of his machine until 1839, when he built a machine imitating the weaving process using the chain stitch.

The first practical and widely used sewing machine was invented by Barthélemy Thimonnier, a French tailor, in 1829. His machine sewed straight seams using chain stitch like Saint's model, and in 1830, he signed a contract with Auguste Ferrand, a mining engineer, who made the requisite drawings and submitted a patent application. The patent for his machine was issued on 17 July 1830, and in the same year, he opened (with partners) the first machine-based clothing manufacturing company in the world to create army uniforms for the French Army. However, the factory was burned down, reportedly by workers fearful of losing their livelihood following the issuing of the patent.[6]

A model of the machine is exhibited at the London Science Museum. The machine is made of wood and uses a barbed needle which passes downward through the cloth to grab the thread and pull it up to form a loop to be locked by the next loop. The first American lockstitch sewing machine was invented by Walter Hunt in 1832.[7] His machine used an eye-pointed needle (with the eye and the point on the same end) carrying the upper thread and a falling shuttle carrying the lower thread. The curved needle moved through the fabric horizontally, leaving the loop as it withdrew. The shuttle passed through the loop, interlocking the thread. The feed let the machine down, requiring the machine to be stopped frequently and reset up. Hunt eventually lost interest in his machine and sold individual machines without bothering to patent his invention, and only patenting it at a late date of 1854. In 1842, John Greenough patented the first sewing machine in the United States. The British partners Newton and Archibold introduced the eye-pointed needle and the use of two pressing surfaces to keep the pieces of fabric in position, in 1841.[8]

The first machine to combine all the disparate elements of the previous half-century of innovation into the modern sewing machine was the device built by English inventor John Fisher in 1844, thus a little earlier than the very similar machines built by Isaac Merritt Singer in 1851, and the lesser known Elias Howe, in 1845. However, due to the botched filing of Fisher's patent at the Patent Office, he did not receive due recognition for the modern sewing machine in the legal disputations of priority with Singer, and it was Singer who won the benefits of the patent.

Elias Howe, born in Spencer, Massachusetts, created his sewing machine in 1845, using a similar method to Fisher's except that the fabric was held vertically. An important improvement on his machine was to have the needle running away from the point, starting from the eye.[9] After a lengthy stay in England trying to attract interest in his machine, he returned to America to find various people infringing his patent, among them Isaac Merritt Singer.[10] He eventually won a case for patent infringement in 1854 and was awarded the right to claim royalties from the manufacturers using ideas covered by his patent, including Singer.

Singer had seen a rotary sewing machine being repaired in a Boston shop. As an engineer, he thought it was clumsy and decided to design a better one. The machine he devised used a falling shuttle instead of a rotary one; the needle was mounted vertically and included a presser foot to hold the cloth in place. It had a fixed arm to hold the needle and included a basic tension system. This machine combined elements of Thimonnier, Hunt and Howe's machines. Singer was granted an American patent in 1851, and it was suggested[by whom?] he patent the foot pedal or treadle, used to power some of his machines; unfortunately, the foot pedal had been in use too long for a patent to be issued. When Howe learned of Singer's machine he took him to court, where Howe won and Singer was forced to pay a lump sum for all machines already produced. Singer then took out a license under Howe's patent and paid him .15 per machine before entering into a joint partnership with a lawyer named Edward Clark. They created the first hire-purchase arrangement to allow people to buy their machines through payments over time.

Meanwhile, Allen B. Wilson developed a shuttle that reciprocated in a short arc, which was an improvement over Singer and Howe's. However, John Bradshaw had patented a similar device and threatened to sue, so Wilson decided to try a new method. He went into partnership with Nathaniel Wheeler to produce a machine with a rotary hook instead of a shuttle. This was far quieter and smoother than other methods, with the result that the Wheeler & Wilson Company produced more machines in the 1850s and 1860s than any other manufacturer. Wilson also invented the four-motion feed mechanism that is still seen on every sewing machine today. This had a forward, down, back and up motion, which drew the cloth through in an even and smooth motion. Charles Miller patented the first machine to stitch buttonholes.[11] Throughout the 1850s more and more companies were being formed, each trying to sue the others for patent infringement. This triggered a patent thicket known as the Sewing Machine War.[12][13]

In 1856, the Sewing Machine Combination was formed, consisting of Singer, Howe, Wheeler, Wilson, Grover and Baker. These four companies pooled their patents, with the result that all other manufacturers had to obtain a license and pay per machine. This lasted until 1877 when the last patent expired.

James Edward Allen Gibbs (1829–1902), a farmer from Raphine in Rockbridge County, Virginia patented the first chain stitch single-thread sewing machine on June 2, 1857. In partnership with James Willcox, Gibbs became a principal partner in Willcox & Gibbs Sewing Machine Company. Willcox & Gibbs commercial sewing machines are still used in the 21st century.

Spread and maturation

Jones Family CS machine from around 1935

William Jones started making sewing machines in 1859 and in 1860 formed a partnership with Thomas Chadwick. As Chadwick & Jones, they manufactured sewing machines at Ashton-under-Lyne, England until 1863. Their machines used designs from Howe and Wilson produced under licence.[14] Thomas Chadwick later joined Bradbury & Co. William Jones opened a factory in Guide Bridge, Manchester in 1869.[15] In 1893 a Jones advertising sheet claimed that this factory was the "Largest Factory in England Exclusively Making First Class Sewing Machines".[16] The firm was renamed as the Jones Sewing Machine Co. Ltd and was later acquired by Brother Industries of Japan, in 1968.[17]

Vintage sewing patterns

Clothing manufacturers were the first sewing machine customers, and used them to produce the first ready-to-wear clothing and shoes. In the 1860s consumers began purchasing them, and the machines—ranging in price from £6 to £15 in Britain depending on features—became very common in middle-class homes. Owners were much more likely to spend free time with their machines to make and mend clothing for their families than to visit friends, and women's magazines and household guides such as Mrs Beeton's offered dress patterns and instructions. A sewing machine could produce a man's shirt in about one hour, compared to 14 1/2 hours by hand.[18]

In 1877 the world's first crochet machine was invented and patented by Joseph M. Merrow, then-president of what had started in the 1840s as a machine shop to develop specialized machinery for the knitting operations. This crochet machine was the first production overlock sewing machine. The Merrow Machine Company went on to become one of the largest American manufacturers of overlock sewing machines and continues to be a global presence in the 21st century as the last American over-lock sewing machine manufacturer.

In 1885 Singer patented the Singer Vibrating Shuttle sewing machine, which used Allen B. Wilson's idea for a vibrating shuttle and was a better lockstitcher than the oscillating shuttles of the time. Millions of the machines, perhaps the world's first really practical sewing machine for domestic use, were produced until finally superseded by rotary shuttle machines in the 20th century. Sewing machines continued being made to roughly the same design, with more lavish decoration appearing until well into the 1900s.

The first electric machines were developed by Singer Sewing Co. and introduced in 1889.[19] By the end of the First World War, Singer was offering hand, treadle and electric machines for sale. At first, the electric machines were standard machines with a motor strapped on the side, but as more homes gained power, they became more popular and the motor was gradually introduced into the casing.

Social impact

Seamstresses in 1904

Before sewing machines were invented women spent much of their time maintaining their family's clothing. Middle-class housewives, even with the aid of a hired seamstress, would devote several days of each month to this task. It took an experienced seamstress at least 14 hours to make a dress shirt for a man; a woman's dress took 10 hours;[25] and a pair of summer pants took nearly three hours.[26] Most individuals would have only two sets of clothing: a work outfit and a Sunday outfit.

Sewing machines reduced the time for making a dress shirt to an hour and 15 minutes; the time to make a dress to an hour;[25] and the time for a pair of summer pants to 38 minutes.[26] This reduced labor resulted in women having a diminished role in household management, and allowed more hours for their own leisure as well as the ability to seek more employment.[25]

Industrial use of sewing machines further reduced the burden placed upon housewives, moving clothing production from housewives and seamstresses to large-scale factories.[25] The movement to large-scale factories also resulted in a decrease in the amount of time clothing production took, which caused the prices for clothing to drop significantly. This is because manufacturers were able to decrease the number of workers needed to produce the same amount of clothing, resulting in reduced costs. Increased supply also lowered the cost.[26]

The initial effects of sewing machines on workers were both positive and negative, however in the long run the negative effects decreased. Many of the women who had previously been busy at home could now seek employment in factories, increasing the income for their family. This allowed for families to be able to afford more sets of clothing and items than they previously could.[26] For seamstresses, home sewing machines allowed them to produce clothing for the average person during periods when demand for fitted clothes was low, effectively increasing their earnings. When industrial sewing machines initially became popular many seamstresses working in factories, as well as those working at home, lost their jobs as it meant that fewer workers could produce the same output.[25] In the long run these now unemployed workers along with thousands of men and children would eventually be able to gain employment in jobs created as the clothing industry grew.[26]

The sewing machine's effects on the clothing industry resulted in major changes for other industries as well. Cotton production needed to increase in order to match the demand of the new clothing factories. As a result, cotton became planted in new areas where it had not previously been farmed. Other industries involved in the process benefited as well such as metal companies who provided for parts of the machines and shippers to move the increased amounts of goods.[27] In addition to being important for clothing production, sewing machines also became important in the manufacturing of furniture with upholstery, curtains and towels, toys, books, and many other products.[27]